What a film!

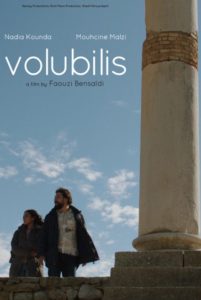

No wonder Faouzi Bensaïdi received most of the awards at the 19th edition of the National Film Festival in Tangier from the festival jury: Grand prix du jury; Award for the script (written by Faouzi Bensaïdi); Best female actor for Nadia Kounda; Best male actor for Mouhcine Malzi; Best original music for Mike and Fabien Kourtzer.

Outside the jury, the film also received Prix de la critique awarded by the association of Moroccan critics, and Prix des ciné-clubs from the national association of ciné-clubs.

As the plethora of awards and triumphant accolades from the National Festvial attest, Volubilis is a film that succeeds and satisfies on multiple fronts : with the public in the theater, the festival people, and the cinéphiles (critics and cine-club goers).

At the National Festival in Tangier, Faouzi Bensaïdi presented Volubilis by describing it as a love story shot in dialogue with the tradition of the Egyptian melodrama – hence his careful attention to music and to structure. As the narrative unfolds, the two protagonists, Malika (Nadia Kounda) and Abdelkader (Mouhcine Malzi) who are in love and poor, will be separated and reunited. Towards the end of the film, there is even a party (in the Egyptian tradition), but it is no wedding with dancing and singing: Bensaïdi twists things with amused irony and the fiesta, instead of a prelude to happiness ever after, leads Malika to the discovery of what her husband has endured. When the haute bourgeoisie feasts, it is on the back of the humble people that it exploits.

The plot is straightforward: Malika and Abdelkader are married. He is a guard in a mall in Meknes, and she finds work as a maid in a bourgeois house owned by a woman whose husband is leaving her. One day, Abdelkader applies the rules and catches a woman brazenly walking past a long line of people waiting for their turn at an office, and orders her to queue up like everyone else. Outraged, the privileged woman vows to take revenge. She does so in the most hurtful way possible, through her husband (played by Bensaïdi himself). The payback for a lower-class man daring to counter a privileged member of the haute bourgeoisie is devastating: individual hogra (humiliation) is explored in all of its possible facets with relentless cruelty.

The filmic narrative also marks a return to the director’s native city: Meknes. The city has grown at different speeds depending on where one lives, since Bensaïdi left: the camera walks us in leafy neighborhoods with opulent villas, in dusty ones with huddled houses in various states of decrepitude, in newly built ones with cold, modern, project housing, and downtown with a modern shopping mall – the access to which the administration wants to restrict to wealthy customers. Only once do we escape from Meknes, when Abdelkader and Malika, cramped in the apartment of Abdelkader’s family, take a bus to Volubilis and walk among its ruins. Malika and Abdelkader can only share intimate moments away from the stifling home. These moments are imaged in delicate, nuanced ways: close-ups on interlaced fingers, of Abdelkader massaging cream into the hands of his beloved, as well as metonymic, extreme close-ups on the mouths of both protagonists sharing a juice. The latter has the erotic power of Gilda’s glove scene.

There is drama, melodrama, humor, beautiful shots and music. Here, the film talks to a wide audience looking for a good story well told.

The film also riffs on other cinemas, with shots reminiscent of Rear Window, of Mulholland Drive, Charlie Chaplin, Jacques Tati, as well as quotations from Faouzi’s own filmography: just as the killer had covered the on-coming sound of a revolver shot in WWW by opening every single faucet in the lavatory, one after the other, mechanically (like Charlie Chaplin on the assembly line of Modern Times), the boss who orders torture covers the sound in a similar fashion by opening all windows looking onto the hustle and bustle of the street below. Two friends try acting like fundamentalists by putting kohl around their eyes (just as they had in Death for Sale). A couple starts a possible love story over the phone, just like in WWW. Not to mention the actors: Bensaïdi himself appears in the film, along with his spouse, Nezha Rahil, who bring their past roles into the decoding of the characters they play on screen. Here, the film talks to film buffs and to those familiar with Bensaïdi’s cinematography. In many ways, the film, solidly anchored locally (Meknes), speaks to an array of people simultaneously, just as Shakespeare did in his plays. The film finds all sorts of ruses to talk to everyone at the same time with impeccable maestria.

Florence Martin