Moroccan films and documentaries are currently really well-represented at film festivals around the world. The TMC team of course screened Aïta and Trances at Africa in Motion (see Will Higbee’s blog); the Kolkata Film Festival in India screened seven contemporary Moroccan films; Volubilis by Faouzi Bensaïdi was screened at Venice and in Carthage and will doubtless visit many festivals worldwide this year; and Razzia by Nabil Ayouch has been selected as Morocco’s entry in the pre-selections for Best Foreign Film at the 2018 Oscars. And these are of course just a few examples: we all know there are some very exciting films to be screened at some of the largest festivals in the world next year.

My most recent festival experience was of six MENA films at IDFA, the world’s most famous international film festival dedicated to documentaries, in Amsterdam. It is one of the most enjoyable, laid-back and convivial festivals I know and I like to visit it every year, mostly because it has always been really good at representing the transnational nature of the documentary industry. From its inception, this festival has had a focus not only on Dutch or European and American docs but also on African, Arab and Latin American, Asian and Australasian films. It really is one of those festivals that make genuine attempts to be all-inclusive and diverse. It avoids red carpet events, focuses on networking events and meetings, and opens up doors both to the industry and to a very loyal and enthusiastic local audience, through affordable ticketing and accreditation. The only downside to the festival, from my perspective, is that it is located in one of the most expensive cities in Europe.

One of my highlights this year was the screening of two modest Moroccan films: Ouarzazate Movie and House in the Fields, on Thursday 23 November. I especially liked Ouarzazate Movie by Ali Essafi, a film from 2001, primarily perhaps because Ouarzazate has been in the news recently, with Noureddine Sail pointing out that Ourzazate as a film location encounters serious issues due to its isolation. In an interview published in English on MENAFM he said: “The problems that hinder film production in Ouarzazate aren’t related to cinema as much as they’re related to the region itself. The region is isolated. There aren’t enough roads to get here. There aren’t enough airline flights. This isolation creates problems. Some international producers come here only because they’re compelled to due to the location’s history with Lawrence of Arabia and other famous films like The Mummy and Gladiator. They say there’s no place where they can film better than this one. We can say that the region of Ouarzazate is like an open studio. But once the issues of transportation put pressure on producers, many of them look elsewhere.” Even as the CCM is now focusing its attention on creating extra incentives through tax rebates and an increasingly professional crew locally, the issue of isolation and a continued lack of communication hamper the studios’ potential.

In the film, we see how foreign film production companies come to this isolated place in the desert, working with local companies such as Dune Films, for setting and location, with or without production incentives. The film focuses on the methods used by these companies to communicate with the local population who are looking for jobs and see themselves as an inherent part of the local film history.

The recruitment process is brutal. The local people are all too willing to be part of a Hollywood production, and they have memories of working on Lawrence of Arabia, or with Paolo Pasolini. One older man in particular reminisces on being Pasolini’s personal assistant and the interviewers become really interested in Pasolini’s attitude towards the man.

He smiles and gives nothing away! The filmmaker also shows the men and women – who are or have been extras in the past – footage of the films they have been in. It becomes clear that they have never seen these films, but it is also exciting to see how they recognise themselves, neighbours, parents, and friends, as people with no specific role but on-screen nonetheless.

Ali Essafi films these hopefuls coming together and competing with one another on a grandstand, putting themselves on display to American, French, Italian and Canadian film producers who have determined beforehand exactly which skin colour, sex and age they need. They survey the crowd as if they were visiting a cattle market. The lucky few to be selected then go on to work crazy hours for a pittance. Women and children are set entirely apart from the men and are treated with more contempt, dismissal and a total lack of empathy by the recruiters than the men, who seem to have formed a hierarchy, with some more confident about their chances precisely because they have been recruited so many times in the past, as they fit a stereotypical image of the generic desert dweller: old, tall and lean, face marked with deep wrinkles and the characteristic beard.

Essafi reveals how communication between production companies internally and between production companies and extras is entirely negligible and one-directional, with no regard whatsoever for the rights and circumstances of their employees, and health hazards are ignored—it’s clearly only about the money, for the foreign companies, not for the locals. Nevertheless, some of the men who have been able to return to several roles on these visiting films have been able to buy or build their houses from their very low wages: each time a pay check comes in they can finish another wall, ceiling or door.

Ouarzazate Movie shows all too clearly that while the films may look stunning on our silver screens, and that foreign productions do indeed come to the studios in Ouarzazate, Saïl has a good point about the actual situation for the local talent and life behind the scenes being entirely neglected and underdeveloped. Once you understand this film, you will look at the famous blockbusters with very different eyes. Western imperialism still reigns unashamedly supreme in the Ouarzazate desert.

—

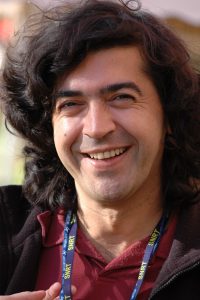

Ali Essafi was born in Morocco in 1963. He studied psychology in France before entering the world of filmmaking. His films include: General, Here We Are (1997); The Silence of the Beet Fields (1998); Ouarzazate Movie (2001); and Shikhat’s Blues (2004). He lives and works in Morocco and Brazil.

Stefanie Van de Peer