The TMC project runs to a close in December 2018. We have had three amazing years where we met and interviewed many Moroccan film professionals. Our last big event in 2018 was the Morocco in Motion conference in Edinburgh, during the Africa in Motion film festival, our amazing partners. We had 15 Moroccan film professionals attending the festival and conference, and reports on their presence and contributions will follow. This blog entry focuses on the young filmmakers that were present, in particular documentary activist Nadir Bouhmouch and animator Sofia El Khyari.

Next to the established filmmakers we were lucky enough to invite to the conference and festival (such as Nour-Eddine Lakhmari, Hakim Belabbes and Farida Benlyazid), we also found it very important to make sure our project at large has been both inclusive and supportive of young filmmakers and young academics. It is the young filmmakers who need support and attention, as they are challenging the status quo and renewing Moroccan cinema from the inside. What stands out to us is that these young filmmakers are investing in non-mainstream forms and genres leading to very exciting developments in Moroccan cinema.

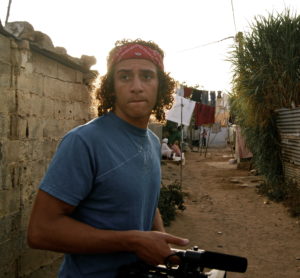

The project has not only offered the opportunity to two young women filmmakers Mahassine El Hachadi and Saida Janjague to spend a term at the London Film School where they developed ideas and networked with other young filmmakers, we have also from the start of the project admired the work of Nadir Bouhmouch – a young filmmaker activist and independent academic who devotes his life to making films outside of the establishment and in opposition to the dominant politics of the CCM. Nadir has also taken part in both conferences we organised, speaking about women’s roles in cinema in Morocco when we held the conference in Marrakech in December 2016, and about the increasing impact of the spirit of neoliberalism in cinema at the conference in October 2018.

His films, especially My Makhzen and Me (2012) and Timnadin for the Rif (2017) have garnered considerable attention internationally, not just for their quality in terms of visual and aesthetic power, but especially for their statements of protest and solidarity with the Moroccan lower classes: farmers, workers, and poor urbanites. My Makhzen and Me is an activist document of the struggle of the February 20 Youth Movement and a daring, direct critique of the Moroccan Makhzen (a popular term for ‘the State’). Likewise, in Timnadin for the Rif Bouhmouch focuses on protest against the unfair distribution of wealth and the neglect of the lower classes in the desert of southern Morocco, where poetry expresses solidarity with the uprising in the Rif. He told me about his work on his new documentary about the longest protest action in the Sahara Desert: a 6-year struggle by the Amazigh population of Imider against the pollution by a silver mining corporation of their already scarce drinking water. It not only portrays a long process and protest, the film is also a labour of love and passion, with Nadir struggling to finish the film on his low budget and without support from any funding institution within Morocco. But he is being encouraged by interest in his work from abroad.

He and his team are confident the film will be finished soon with the support he receives from friends and his strong determination to get it out. As a research team, we really hope that the exchanges with producers, distributors and festival organisers at the conference and throughout the project have enabled him to speak to and – importantly – be heard by those with power and money, so that he can successfully change the future of documentary and freedom of speech in Moroccan cinema. He said he hopes he gets more such opportunities to speak up, and found the platform of the project ‘necessary, and even urgent.’

The Transnational Moroccan Cinema project has been funded by the AHRC, and their funding has enabled us to do lots of events over the three years. We have held big conferences, smaller workshops, film screenings, film festival panels, and have been able to visit a large number of Morocco-based festivals in order to discover more about the Moroccan film scene. At one of these festivals, FICAM in Meknès, I had the pleasure to meet Sofia El Khyari and see her first film Ayam. It is only three minutes long but very powerful – as it deals with the love between generations of women over the course of a short tea ceremony.

Sofia was educated in France and in the UK, and has had some success on the festival circuit with Ayam, winning prizes not only in Morocco but also in France and further afield. She recently finished her graduation film for her Master’s degree at the Royal College of Arts in London. The stunning The Porous Body (2018) explores the outer limits of the body, searching for the space where the skin touches its surroundings and the level of porousness of skin, while also exploring the power of water and the sea as a symbol for womanhood and the subconscious. The film artistically and experimentally deals with space, place and belonging, and with girlhood simultaneously developing into, embracing and rejecting womanhood. The technique of animated watercolour and using watery colours when depicting events and figures outside of the water, interspersed with live-action in filming scenes under water, challenges our ideas of perception and representation. Sofia describes the film as a poetic meditation, and it certainly makes the viewer think and the skin tingle as it increases an awareness of the outer layers of the human skin.

Sofia told me she was excited to be part of the project and happy that she was invited to screen Ayam at Africa in Motion and speak at the conference, alongside Farida Benlyazid and Lamia Chraibi. The panel she was on at the conference discussed the status of women in Morocco and in the film business at large, and was chaired by our very own fearless woman, Flo. Sofia’s contributions as a young, strong and experimental filmmaker were central to the realistic vision of the future of women in Moroccan cinema, and she told me she felt like she was part of something that increasingly interests her. Being transnational in her education, her knowledge and experience of Moroccan cinema was limited, but meeting inspiring women like Lamia and Farida has ignited her exploration of the Moroccan film world.

The project that we have run over the past three years has seen us meet the big names in Moroccan cinema and those well-established, both historically and contemporarily. But for me, what has stood out and what has really excited me is the energy of the non-mainstream film festivals, and especially the strength and the vibrancy of the young filmmakers and academics I met. I cannot wait to see Nadir Bouhmouch’s new film and explore more of Moroccan animation – especially young women’s roles – such as Sofia El Khyari’s, in the future of animation.

Stefanie Van de Peer