In the latest production of Moroccan cinema, father figures seem not to fare very well. For instance, in Nabil Ayouch’s Horses of God (2012), the father is impotent, silent, at the mercy of his wife and children for sustenance; in Noureddine Lakhamri’s Zero (2012), he is an invalid entirely dependent on his son to survive. The films shown at the 17th National Film Festival in Tangiers show a similar, consistent, relentless trend. To wit:

Tears of Satan (Hicham El Jebbari, 2015) is an action-packed road-movie that narrates the revenge story of a former prisoner who finds his torturer from the years of lead. In a stunning reversal of the Abrahamic myth, the same hyper-masculine torturer ends up killing his own son, before being killed himself. Here the masculine authority figure is completely destroyed, harrowing moment after harrowing moment.

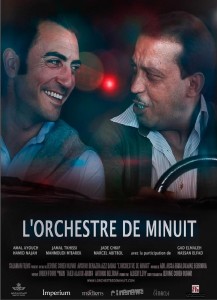

In Midnight Orchestra by Jérôme Cohen Olivar (2014), musician Marcel Abitbol, the father of protagonist Michael Abitbol, dies within the first four minutes of the film! If the rest of the film tries to piece together why Marcel abruptly left Casablanca in 1973 (to the sound of Marcel Abitbol’s music), it does not show the death of the father: it shows the dead body, the aftermath, the homage to the father, while the father himself is largely absent from the screen.

Such is not the case in Hicham Amal’s Morphine Melody (2013), that features a young composer who, after losing his inspiration to compose and yen for life, finds new creative ideas for his opus magnus from the very cries of pain of his dying father. Here, although he is heard a lot, he is ill, powerless, dependent and facing his impending death. In that, he is the same father as Ayouch’s or Lakhmari’s, or, for that matter Mohamed Ismaïl’s Des…Espoirs / Despair (2015) powerless, and destitute father figure. In this film, the protagonist’s father is alcoholic, poor, passive, and dominated by his second wife (after she first abandoned him and his son, Amine). Eventually, he is slain by her in front of his son. The ensuing trauma causes Amine to have serious problems with women throughout his life.

A father’s premature death causes irreparable damage to his children, as is also clearly shown in Mohamed Chrif Tribak’s Petits Bonheurs / Happy Moments: the father has just died at the opening of the narrative and his absence entails economic and emotional hardship on his young widow and teen-age daughter.

Again, in Saïd Khallaf’s A Mile in My Shoes, the protagonist’s father dies when Saïd is a child. Saïd murders his stepfather (an ogre-like character who embodies the bad father-figure). Yet the assassination is literally staged: the film juxtaposes theatrical scenes with non-theatrical ones, and the death of the father is filmed like a ritualistic murder on an empty stage, lit by an unforgiving spotlight. This film won the grand prix at the National Film Festival.

Finally, I’d be remiss if I did not mention Driss Chouikha’s Resistance, a national epic about decolonization that starts in 1953. The hero, Abderrahmane, a young freedom fighter, has lost his (good) father who died at the hands of the French, and marries a young woman whose father is a collaborator of the colonizer. Abderrahmane’s people execute the (bad) father-in-law (causing some degree of discomfort in Abderrahmane’s marriage…). In this film, the masculine figure of undisputed authority, the King, is only perceived via the roaring engine of his approaching plane above, and cheers of the expectant crowd amassed below. Here, the absence or remoteness of the good father verges on the sacred. The filmed death of the father is only that of the bad father. The good father remains soundlessly off screen, untouched.

Florence Martin