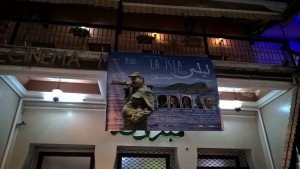

On February 17, 2015, I met Abdellatif Labbar in the old theater district, a stone’s throw away from the Rialto. This delightful gentleman who used to program the films that were screened in Casablanca, reminisced about the golden age of cinemas in his fast-changing city and explained why Indian films were screened in Morocco.

“I was in charge of programming the films to be screened in Casablanca. There were over two hundred movie theaters in the Kingdom. Today we only have a little over fifty screens…” [fifty-seven, according to the Centre Cinématographique Marocain]. “Too much piracy and too little interest perhaps… People have changed… Look at the many old cinemas of Casa: the Rialto, the Vox, the Empire, the Colisée, the Lux, the Verdun… most of them are closed now, although in theory, a movie theater cannot be closed.

In the old days, we programmed films from the US, France, Italy, from all over Europe, but also, of course, a lot of Egyptian films. People loved swashbuckling films, American westerns. Each time we screened a film by Charlie Chaplin, it was always a hit! And it was a hit for a long time: people adored him! Some of the oldies, like Ben Hur or the films with Sidney Poitier were so popular they had a five-week run, especially in the summer… There were other sorts of hits: I remember Z by Costa-Gavras (1969), in particular. It arrived on Moroccan screens only in 1972. But the censors took it down on its second day of release. Too politically charged after the failed attempted coups against Hassan II [the Skhirat coup on July 10, 1971 and the aborted putsch of August 16 1972, dubbed “le coup d’état des aviateurs”]… When the film was reissued ten years later, people flocked to it! And it showed at the Rialto and the Vox for weeks on end.

Cinema dealt with language in an interesting way: the Moroccan audience saw the French versions of the films coming from the United States. Gone with the Wind, for instance, was dubbed in French. So were the westerns with John Wayne. Only a handful of French films were dubbed in darija to accommodate the local audience – Fantômas and later Fanfan la tulipe come to mind – otherwise, most French films were screened in their original versions. The same went for Egyptian films, of course. Moroccans, like other people in the Arab world, learned the Egyptian dialect via Egyptian radio (Voice of the Arabs), TV and cinema.

In 1963, however, Morocco and Algeria fought on border issues. Egypt, recently independent and led by Gamal Nasser, sided with the Algerian FLN against Morocco. In reprisals, the Kingdom broke all diplomatic ties with Egypt. As a result, we could no longer import Egyptian films. This is when Morocco started to import films from India massively, and dub them in darija. We were inundated with Indian films! Lots of Indians had moved to Tangier when it was an international city, had married Moroccan women and settled in various urban centers throughout the Kingdom. Some of their translations were hilarious!”

Florence Martin