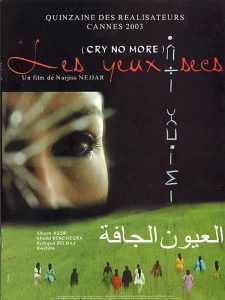

This article aims to cast light on Moroccan women’s cinematic voices; and in particular Narjiss Nejjar. Thanks to her accumulated filmography, she is nowadays considered an active member of the Moroccan women’s film community. Her debut feature film al-Oyoun al-Jaffa (Les Yeux secs/ Dry Eyes, Morocco and France, 2003) is widely acclaimed. With a focus on this film, I argue that it negotiates female spectatorship through two main strategies. First, it represents women as full-fledged citizens away from any process of eroticisation or fragmentation. Second, it pushes the spectators, male and female, to identify with the female characters through this strategy of representation. To identify with Nejjar’s female characters, one has to identify with their journeys of becoming.

Les yeux secs (2003) tells the story of some women who sell their bodies in the Middle Atlas, exactly in Tizi village; they are geographically and socially marginalised beings. Apart from the prostitution business, they have no other source of income. “The only men allowed to enter the village are those who pay for the women’s services” (Hillauer, p. 358). Their community is led by the young Hala, acted by Siham Asif, who dictates the rules and gives the orders. About the age of thirteen or fourteen, Zainba, Hala’s daughter, is the only teenage dwelling in the women’s village. Hala’s mother, Mina (played by Fatima Harrandi), is an old woman who returns to the village after a long time of absence.

Dry Eyes does not only spot the process of becoming-woman by women, but by men as well. Nejjar, quoting Orlando, “leaves her characters before a tabula rasa on which to remake their identities, destinies, and gender roles. Both male and female roles are equalized as they face the challenges of building a new identity and destiny for themselves” (2011, p. 135). Not only are Nejjar’s characters a tabula rasa, but also Morocco itself is so since its identity is never fixed. Fahd, an Arab who comes from the central Casablanca, throughout the film, tries to prove to Hala that he is not a member of the brutal men she has been receiving at her own home. To show his deep sympathy towards the females, Fahd “loses his traditional masculinity by affectively connecting to the emotions of the women” (Pisters, p. 86). To make his good intentions clear to Hala, he “dresses in drag (complete with eye make-up and badly applied lipstick) in some kind of symbolic taking-on of the prostitutes’ pain, which also involves him dancing and screaming naked on a snowy mountain top” (Armes, 2006, p. 155). Being stripped in a snowy high space could be read as a moment of catharsis for Fahd as he fails to rescue the young Zainba from being deflowered, and to change the women’s disquieting destinies. Dry Eyes, Patricia Pisters points out, asks for a becoming-woman of both man and woman so as to help the country move into the future (p. 86).

Becoming-woman in Nejjar’s work goes hand in hand with becoming-Berber, or what Pisters names “becoming-minoritarian.” She argues that it is striking that “in many of the contemporary films made by transnational female directors, there is a double focus of women and Berberity.” Hence, she sees “these two new aspects of Moroccan cinema as two phenomena of “becoming-minoritarian” of national cinema and perhaps of the Moroccan nation” (p. 77). In a similar fashion, the focus in Dry Eyes is put on both women and Berberity. The film’s journey of becoming-Amazigh starts from its very beginning. It is telling that the first voice heard in the film’s first scene is that of a female Amazigh woman, Mina. Nejjar’s film, accordingly, highlights the two issues of women and Berberity. The beginning credits are accompanied by the Ageggig song, sung by the well-known Algerian Amazigh singer: Idir. Opting for a well-known Maghrebi song can be read in two ways; first, it can be chosen for its sad tone so as to signify that the film’s narrative revolves around a melancholic story. Second, it might be chosen by Nejjar in order to emphasise the Maghrebi countries’ Amazigh origins.

Being a postcolonial text, Dry Eyes negotiates women’s representations and female spectatorship within cinematic works. Away from any eroticisation or fragmentation, women are represented as full-fledged citizens with whom the spectators, males and females, do identify. They lead the narrative, control the gaze, and make meaning; they are not the spectacle. In Nejjar’s film, the female protagonists are dynamic; their life experiences are marked by processes/journeys of becoming. As it is the case in postcolonial and cultural studies, identity in Les yeux secs is never completed or fixed. Rather, it is in a continuous process of formation. It has, as Madan Sarup argues, to do with becoming, not with being (p. 94). Dubbed as journeys, identities in the film are linked with the idea of becoming. The journeys analysed include ‘becoming-Moroccan,’ ‘becoming-woman,’ and ‘becoming-Amazigh,’ which do reflect the unfixity of the postmodern subject’s identity/identities.

References:

Armes, Roy, 2006. African Filmmaking: North and South of the Sahara. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Hillauer, Rebecca, 2005. Encylopedia of Arab Women Filmmakers. Trans. A. Brown, D. Cohen, and N. Joyce. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Orlando, Valérie, 2011. Screening Morocco: Contemporary Film in a Changing Society. Ohio: Ohio University Press.

Pisters, Patricia, 2007. “Refusal of Reproduction: Paradoxes of Becoming-Woman in Transnational Moroccan Filmmaking.” In: K. Marciniak, A. Imre and A. O’Healy, eds. Transnational Feminism in Film and Media. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 71-92.

Sarup, Madan, 1994. “Home and Identity.” In: George Robertson et al., eds. Travellers’ Tales: Narratives of Home and Displacement. London & New York: Routledge, 89-101.