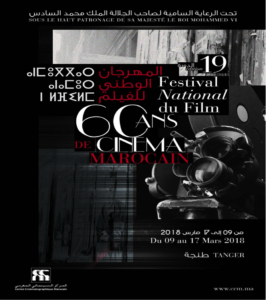

Moroccan cinema is celebrating its 60th anniversary this year. It was the highlight of the 19th edition of the National Film Festival in Tangier (9-18 March 2018). Something else was visible in Tangier: Moroccan cinema is a house divided against itself.

Attended by the 4-member TMC team, the festival showcased the diversity of Moroccan cinema today by screening over 30 long and short films produced over the last 12 months. Films ranged from the finely executed (House in the Fields,Volubilis), the experimental (Jahiliya), the hollow and prententious (Razzia, Burnout, The Howl of the Soul), to the avowedly simple and popular (Korsa,Lahnech). The annual festival also revealed some cracks and structural problems in the edifice of Moroccan cinema. This should in no way be interpreted as meaning that this divided house will not stand for a few more decades.

Born out of the ashes of colonial cinema and the urgency of nation-building following the country’s independence in 1956, Moroccan cinema has grown spectacularly over time so much so it resembles its old self less and less every year. The identity of Moroccan cinema today is multifaceted; it has no single direction or common style. This diversity was there for all to witness during the national film festival in rainy old Tangier in March. The first category of films on show consisted of ‘made-for-TV’ comedies and dramas meant for a Moroccan audience first and foremost. The veteran actor and filmmaker Abdellah Ferkous (b. 1965) was at it again with his widely appreciated Korsa (2018). The mere presence of Ferkous in the male lead role of the film was enough for the movie to get the audience hooked to their seats. The road-movie comedy follows on the footsteps of the previous Ferkous box office hit El Ferrouj (2015).Korsauses the same recipe for success by tackling topical societal issues from below whilst shying from technical experimentation.

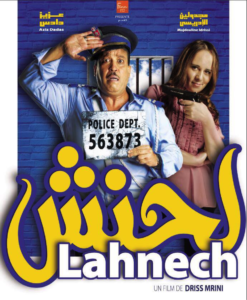

The second comedy is set in Rabat, which has recently become a familiar site in Morocco cinema. Even though Lahnech had been released and widely watched in national cinema theatres since early December 2017, it drew huge crowds to French-owned Mégarama’s Tangier multiplex for two simultaneous screenings in the late evening. The film uses a constellation of popular actors in the main roles including Aziz Dadas and the eternally young Majdouline Idrissi. Dadas plays the central role as a fake traffic warden. The actor is a popular face on Moroccan television and cinema. Much like Ferkous, he is perceived as weld cha’ab(lit. ‘son of the people’), hence his popularity and ability to represent the majority of Moroccans. Class is increasingly becoming a dominant lens through which Moroccans perceive themselves on screen.

The other category of films at the national film festival was made of ‘world cinema’ products clearly made to satisfy international audience tastes and hopefully some domestic ones as well. This second category is sometimes labeled ‘festival cinema’. It is frequently attacked in the local media and by Morocco-base intellectuals for some of its films’ militantly exotic and occasionally Orientalist framing of Moroccan culture and society. Film critics love to hate them with few exceptions. However, these films are often appreciated at festivals even in Morocco, where they usually win first prizes including at the national film fest, thanks to technical quality and aesthetic accomplishment.

The film which won most prizes, including the Grand Prix, in Tangier this year is Volubilisby Faouzi Bensaïdi. The film has been widely acclaimed by film critics in Morocco since its premiere in Rabat in November 2017. As the Paris-based Bensaïdi admitted in an interview with the TMC team on the morning of the prize announcement day, the film is one of cinematic maturity and has been made with a wider audience in mind. However, Bensaïdi warned us that the next film would be like his previous essay works prior to Volubilis.

Other remarkable films of this second category on show at the national film festival this year were House in the Fields (2017) by Tala Hadid. The documentary lovingly chronicles the everyday and breathtaking natural beauty of an Amazigh village in the High Atlas. The central characters are Fatima and Khadija. The former is getting ready to be married to a village youth who works and lives away in Casablanca. The film portrays the characters and their environment with much love and a subtlety that is often lacking in films about the Atlas mountains. It should have own more than the festival’s Editing Prize. Hadid’s first feature film The Narrow Frame of Midnight won the festival’s Grand Prix in 2015. Another film in this category which is also partly set in the High Atlas is Nabil Ayouch’s much mediatised Razzia(2017). It hugely disappointed a large section of the festival audience due to its runaway narrative fragmentation and reduction of Morocco to a few clichés (backward Berbers, Muslim fanatics, anti-Semites and prostitutes) to satisfy the average western viewer’s image of Morocco. More successful and appreciated was Narjiss Nejjar’s fourth feature film Apatride(2018). The story of a 34-year old woman bent on finding her Algerian mother from whom she was separated when 45,000 Moroccans were banished from Algeria following Morocco’s annexation of the Spanish-occupied Sahara in 1975, Apatridewon the Production Prize for Lamia Chraïbi. Chraibi also won the same prize for Jahiliya(2018) by Hicham Lasri, who reaped the Director’s Prize.

It is clear that the type of audience the filmmakers have in mind has come to define the look and nature of Moroccan films. The CCM has encouraged this division since the early 2000s by awarding funding to both popularand festivalcamps of Moroccan cinema. The commercial films like Korsaand Lahnechare meant to entertain domestic audiences and thus keep film houses in business. The arthouse and/or transnational films like Volubilisare there to represent Morocco in the international scene by featuring and hopefully winning prizes at global film festivals. Despite this policy, the CCM and filmmakers in both camps have entertained the desire to speak to all audiences and therefore create a more cohesive Moroccan cinema. This explains the popular edge in Bensaïdi’s Volubilis. The film has not yet be released in national cinemas, but it is not likely to do outstandingly even though it is significantly more accessible than the director’s previous works. No film has succeeded in satisfying international and national audiences at the same since Nabil Ayouch’s Ali Zaoua(2000). The CCM has not been able to help. No one seems to know exactly the success formula, including Ayouch who has not able to replicate his rare accomplishment. Hence the sense of division and loss of direction in Moroccan cinema. Filmmakers will have to keep trying hard to bridge the gap between Moroccan and international viewers and points of view. Meanwhile, Ferkous will go on making his popular comedies and Bensaïdi his cinephilic essays.

Between the two categories, a lot of films fall through the cracks. They are forgotten almost as soon as they are made. They neither win prizes internationally nor attract filmgoers at home. Unfortunately, this represents the third and major category of Moroccan films today. The CCM needs to find a way to reform this part of Moroccan cinema’s divided house at 60.

Jamal Bahmad