Aside from last week’s discussed feature-length films that attract full audiences and long discussions with filmmakers, sometimes serious and sometimes dominated by the kids in the room, we also followed the exciting experiments that were showcased in the short film competition at FICAM. In the second batch of shorts screened on Sunday evening, we saw the usual (great!) French, Canadian and Croatian work, but to be completely honest, we were there specifically for the Moroccan short, Ayam / The Days, by Sofia El Khyari.

On occasion, the festival has included screenings of local productions in the past; for example – as Paula Callus has shown, in 2002 Hamid Semlali’s L’oiseau de l’Atlas (The Bird of the Atlas, 2002) was screened. Semlali’s ten-minute film was exceptional on two counts: firstly as a rare example of a local animation screened at an international festival, and secondly as a case of a Moroccan animation receiving funding from the CCM (100,000 dinars). But these films are rare, and so the hunger for Moroccan animations is huge at FICAM. The excitement about Sofia El Khyari’s film was palpable as she introduced the film.

The director of the festival was equally excited about the presence of a Moroccan film in the short film competition, and Alexis Hunot, doing the introduction to the screening of the selection, encouraged everyone in the room to vote on their audience voting slip, adding that of course they would be expecting to see many vote for Sofia’s film.

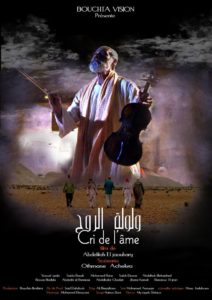

Born in Casablanca in 1992, Sofia El Khyari left her native Morocco for Paris after she finished school. She trained in creative industries management and taught herself animation with various workshops in France. She spent time in China and then settled in London where she is now pursuing a master’s degree in animation at the Royal College of Arts in London, where Ayam was made. Ayam uses mixed-media paper cut-out, stop-motion, acrylic paint and soft pastels, ink and crayon on brown paper in an animation that combines elements of old school Asian anime films as well as distinct Moroccan aesthetics such as soft contours, bright colours, decorative backgrounds, geometrical shapes and organically flowing lines and calligraphy.

The filmmaker told her audience that the film is inspired by her mother and grandmother, and their love for one another and for her, and on the anecdotal nature of conversations, stories and history-telling in her house, in particular during the traditional tea ceremony of Eid Al Adha. Indeed, El Khyari seems to be mostly interested in women’s particular perceptions of the world, as her previous work, available here, elaborately shows. Curious about everything cosmopolitan, she develops a mixed dream world where the female figure is queen.

In Ayam this becomes very clear, and in this film the main inspiration is women of older generations: her mother and grandmother. The film is dedicated to the female characters in her life, and depicts in three and a half short minutes, the preparation for the tea ceremony. Grandmother and mother talk about the glasses being clean, the tea hot and the table being set, as the young daughter remarks she thought that grandmother could not read because she has never been to school. It quickly becomes clear that grandmother is from an age where women were not encouraged to go to school, but that she was pragmatic enough to make sure she learnt reading and writing on her own terms, from her older brother, when he came home from school. Likewise, the mother figure shows how having a daughter now is crucial to her own role as a woman, and she has sacrificed her own ambitions to ensure her daughter can go to school and encourage her to get the best grades she can. In return, the granddaughter shows her love for her mother and grandmother by representing them in a stunning short documentary tale of cross-generational solidarity and warmth. Especially in the subtitles, which are encased in elaborately decorated frames, and in the calligraphic elements that come to life in the film and show the beauty and importance of Arabic script. In an interview, Sofia told me she thought long about what to do with the subtitles, as she studies in Britain and is aware of the dislike of British audiences for subtitles. Her tutor recommended she make a feature of the subtitles, as part of the mixed-media aesthetic of the film. Sofia then sought inspiration in ancient Arab storytelling, the 1001 Nightsin particular, and created paper-framed text for the subtitles, an inherent part of the beautiful aesthetics on screen.

This interest in the written word is also reflected in her use of calligraphy in the abstract art backgrounds of the otherwise figurative depictions of the women. This is especially interesting if we read it in the context of Laura Marks’ theory on calligraphic animation, and the importance of calligraphy in Arab animation at large. As Marks says: ‘many artists are bringing Islamic textual aesthetics to contemporary media art, and thus they are enriching this art’s qualities of latency, performativity, and transformation’ (2011). Marks showed how one of the most popular non-figurative Islamic arts, calligraphy, in many respects is in itself animated: its written words or single letters encapsulate life and movement in their fluidity. Calligraphic artworks, while they do not depict living forms, do embody the movement of life itself. ‘Watching calligraphic animation, we feel empathy with the letters as they swoop free of their symbolic constraints and become animated, take on (non-organic) life’ (2011). In this view, letters have inherent meaning: the meaning is there behind the surface of the animated image, in the code.

Ayam has already done the rounds at some of the most important animation film festivals in the world. It also screened at the Cardiff Animation Festival in Wales this past week (19-22 April). It won the audience award at FICAM in Meknès. The filmmaker’s parents were present and obviously very proud. Sofia said she wanted her parents to come along to the screening, as her journey towards becoming an animation artist has been a long and hesitant one, because family and friends have worried about the financial viability of a career in the arts and animation. Yet she deeply believes in the value of the animated image, and has done so since she was only 15 years old. The animator dedicates time to all aspects of her animated art: she composes the music and sings for her own films, she explores different media and art forms, and harvests inspiration from all over the world. She is aware of the practical obstacles to young Moroccan filmmakers in general, and animators in particular, but hopes to continue to meet the right people who she can enthuse about her stories and styles in the future. She is currently working on her graduation project from the Royal College of Art, which will focus on the relationship between women and water. She is researching specifically Arab women that can be an example to her art and her ambitions and while she wants to work in Morocco, she is mostly interested in international co-production in order to maintain the inspiration flowing beyond borders and in order to maximise other areas’ increasing interest in funding and supporting new and young animating artists.

Sofia also recognised, in this context, that one of the things FICAM does so well is organise workshops and presentations, and network opportunities for students and young artists. It is very well-organised, timetabled and accessible for children as well as students and the wider public. Quite the relief after the “private” festival that is the FNF in Tangier, where the public is not allowed anywhere near the cinema. The amount of young Moroccan students of animation, walking around at FICAM with their portfolios under their arms is exciting to see.

That’s why, after one of the best presentations of the festival, by Rachid Naim from the University of Safi, on the representation of the Arab in American animation, the discussion’s turn to the lack of Moroccan animation was so surprising to me. Firstly, Rachid’s presentation was eye-opening. Not in the sense that he broached a subject that we are all very familiar with, namely the racism in Disney’s Aladdin and the problematic depiction of the “bad” Arab in Hollywood, but in the sense that he gave me, personally, a fresh new insight into his vision of Orientalism, with references to so many others than Edward Said. He elaborated on the creation of the 1001 Nightsand their origins, not as Arab tales but as being from all over the Middle and Far East, or the invention of Ali Baba and Sindbad by the chroniclers, French and British. That these characters are ‘good’ guys in the 1001 Nightsand become bad guys in Popeyeand Bugs Bunnyfilms adds interesting materials to Jack Shaheen’s famous work on Hollywood’s “Reel Bad Arabs.” The discussion after Rachid’s talk turned very animated when Alexis Hunot pointed out that there is no Moroccan animation. Clearly Sofia El Khyari’s film contradicts this throwaway statement, and the presence of so many ambitious students does as well. I was itching to point this out to him, and so did the students. My good friend Paula Callus has of course also written a rich chapter on Moroccan animation in the edited collection on Arab animation, so there certainly is more than Alexis acknowledged. I wonder if it was a tactic on his part to encourage the students to really pursue their animation dreams. FICAM is certainly the right place to do so, as it is one of the only platforms in Morocco for animated cinema. Long long long may it live on and celebrate animation from Morocco!

Source:

Laura Marks, ‘Calligraphic Animation: Documenting the Invisible’, Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 6, 3 (2011), pp. 307-323.