Riding the train from Rabat to Casablanca for the first time, my eyes are glued to the train window, even if the latter has seen better and cleaner days: a yellowish haze filters the screen of the shifting landscape. Past the station of Mohammedia, the surroundings change from industrial wasteland to “residential”: the first bidonville appears (the term first appeared in French to qualify the slums of Casablanca, as the city sprawled from a mere 20,000 in 1907 to today’s 2.5 million and counting), and will be followed by many more, huddled along garbage dumps where the refuse of the neighboring urban centers is piled high and oozes past the main heap in all directions. My surprise comes from a feeling of déjà vu: I recognize the slums of Nabil Ayouch’s Horses of God, of Yassine Fennane’s Karyan Bollywood. I register the patchwork of roofs sprouting with satellite dishes in haphazard rows like invasive weeds.

Once in the city, riding a petit taxi to my first appointment downtown, I soon find myself in one of these famous Casablanca traffic jams: noisy, utterly chaotic, but again not startling, a pale version of those in Noureddine Lakhmari’s Zero (I do get slightly concerned, however, when my taxi abruptly jerks to the right to follow the shiny black Audi that has just inaugurated a third lane in a two-lane boulevard).

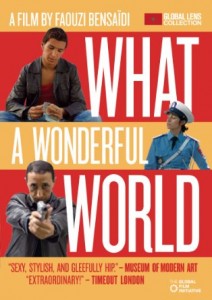

I reach my destination near the Twin Center and, upon seeing the twin towers of Casablanca, realize with a twinge of disappointment that Bensaïdi’s What a Wonderful World had made them taller, more foreboding, whiter! My filmic familiarity with them now morphs into a bizarre nostalgia for a place that never was: a filmic fantasy achieved with a bright filter, larger than life.

On my way to another appointment, I pass restaurants and cafés that spring out of Nabil Ayouch’s Ali Zawa, Noureddine Lakhmari’s Casanegra, and finally What a Wonderful World, the café in which Kamel waits for Kenza. At that precise moment, as the taxi is going around the circle in front of the – by now for me mythical – brasserie, it starts to rain heavy drops, vertically, very much like the selective cloud that empties itself exclusively over the two protagonists in WWW.

The cinematic bubble of Casablanca has taken over the physical Casablanca in which I find myself. Puzzled by this form of cine-tourism to which I have unwittingly fallen prey, I nonetheless keep identifying sights from film and film from sights, at each turn in the city. It will take several more ventures to Casa to reel the films back and start to see the city afresh, no longer a movie set…

Florence Martin